Longboat Key

At some point it became tradition for my family to vacation at Little Gull, a small resort located on the island of Longboat Key, Florida. The exact origins are unknown to me, as my first recollected beginnings there date back to when my family was quite familiar with the place. I was the youngest of five children, and my siblings already had a rich history with the island, annually spending a week there shortly after the Christmas holiday. It was a warm, tropical respite from the snowy climate upstate, and my family would rejoice at being reunited in paradise.

Funnily enough, my initial fascinations with the island were at night, however. At a young age I was captivated by these multicolored lights that lined the brick walkways to each cottage. Shrouded by brush, they illuminated the path with red, blue, yellow and green. One of my oldest memories is walking this path with someone in my family, although I don’t remember who. The haziness of this particular memory is unsettling to an extent, as I’m sure that at one point I knew that it was my brother. Or was it my father?

The Longboat Key tradition continued as I grew older. But as each year passed, members of my family phased in and out, often kept away from the island due to different obligations. Despite some years where our party was a mere four people, the theme of our stay remained the same. The island was a place for reunion, a rejuvenating microcosm where the entire family seemed to become one, again. Bound by the sound of the waves and the feel of the sand, my family was consistently enriched by Longboat Key, its poetic nuance and its playful capacity strengthening our bonds. For me, it was a special place like no other.

As I reached adulthood, my relationship with the island grew more complex. Through elementary and high school, Longboat Key was a “school vacation,” that blissful and universal festival that liberates a student. But as I entered college and began my journey towards independence, the gestalt of the experience spurred my photographic pursuits. I became increasingly aware of the passage of time, indicated by my family. No longer was I the youngest of the group, my new title as an uncle finally making an impression on me. My nephews, each unique from one another, inspired me to take photographs.

Through photography, I developed a sense of context. Ephemeral interactions with the environment revealed moments that were familiar and distinct. A fog covers the bay, a red bucket left behind on the table. A strong tide in the fog, a beach renewed with treasures for my brother and his son to explore. Consistent revisitation of the island may have eroded some of my memories, but these pieces of time reappear and intersperse, coalesced as a new sense of the island, my family and myself. But there is always a barrier, a point of impossibility in that sense. What does my family see?

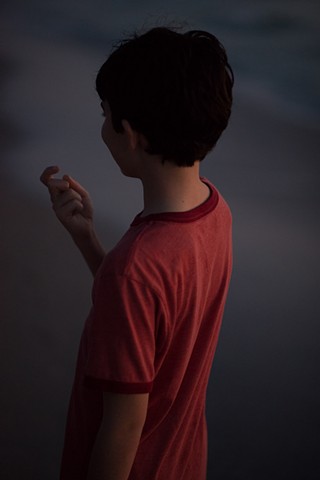

Last year, my youngest nephew walked on the white beaches under an overcast sky, and quietly stared into the distance. I do not know where he sees, but I understand something unique to him and only him, something that I will never see. I can only stand behind his back, intuitively understanding that he is thinking, yet having no idea what composes his thoughts. Similarly, I can stand at a distance from my eldest sister, photograph her onlooking, and only after the fact realize that her expression resembles a nostalgic sadness. But again, I will never see what she sees.

As a viewer of this series, I am intrigued by the idea that these photographs are intimate and detached. There are only glimmers of understanding, a metaphysical distance in flux between each member of my family and the camera. But I seek to form a relationship nevertheless, an almost anonymous presence looking in and looking out. Amidst the vastness of a ocean before us, past the waves of the water that lap against our feet, we meditate on what we see, and what we see in others.